India

More than two years after violence erupted, members of the feuding Meitei and Kuki-Zo groups in India’s Manipur state remain divided by more than their respective relief camps.

By Angana Chakrabarti, Reporting Fellow

Kshetrimayum Dinesh and his father run a food stall outside the Khoyol Keithel relief camp in Moirang, while Lamjahat Haokip collects laundry at the Sadbhavna Mandap camp in Churachandpur.

MANIPUR STATE, INDIA — Lamjahat Haokip and Kshetrimayum Dinesh live nearly identical lives. The young adults each come from a community that opposes the other, both were forced from their homes by the violence, and both now live in relief camps that are just 17 kilometers apart (10.5 miles).

Dinesh is from the dominant Meitei community, and Haokip is of the Kuki-Zo group. In May 2023, violence erupted along the border between their communities in India’s northeastern Manipur state. The clash followed a protest earlier that day led by several tribal groups who opposed efforts by the Meitei community to attain Scheduled Tribe status, which could help Meiteis benefit from quotas for government jobs and college admissions. Opponents say the move would lead to the larger community getting more preferential treatment.

“I was involved in the stone-throwing,” Dinesh admits. He and his family left their home overnight, for fear that the people from the Kuki-Zo group would attack. They’ve been living in a relief camp since then.

Haokip, meanwhile, feared that day that a mob of Meiteis looking for Kuki-Zos would attack the hostel where she lived while attending school. The mob did come, and Haokip managed to escape to a friend’s house. Then, she too landed in a relief camp, this one for Kuki-Zos.

The feud is the longest-running of its kind in 21st century India; it has left 260 people dead, nearly 60,000 people displaced and thousands of people injured.

Over the course of two months in 2023, entire villages, including Dinesh’s and Haokip’s, were razed. Weapons were looted from police stations. Meiteis living in the hills fled to the valley, and Kuki-Zos living in the valley were forced to the hills. The conflict shifted to intermittent gunfire in the foothill areas, prompting civilians to tote firearms.

On the stretch of road that separates Haokip’s and Dinesh’s camps are at least four checkpoints manned by five different security forces who have been standing guard day and night. The short distance is nearly impossible for either to cross, yet their days mirror each other.

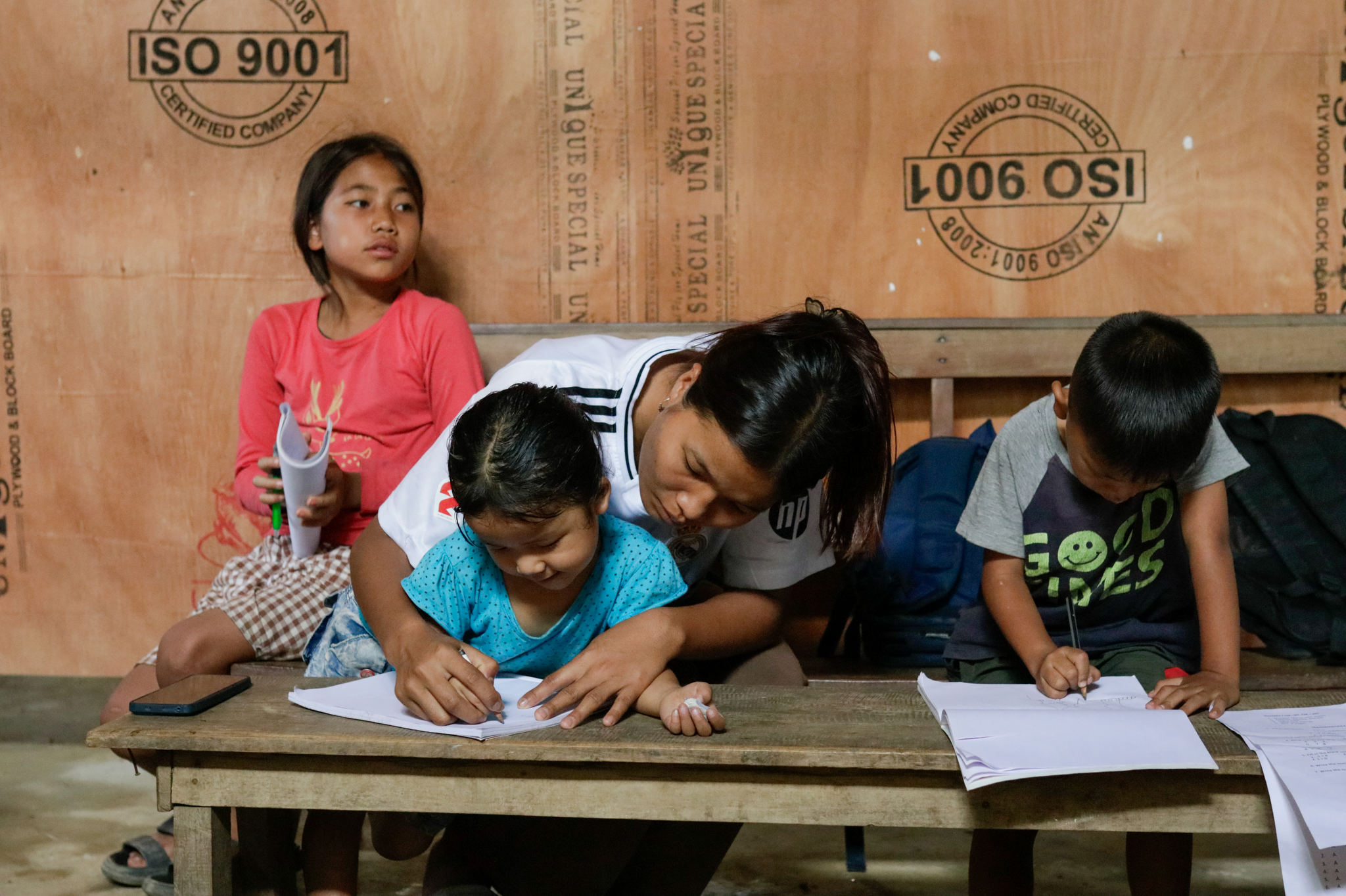

Dinesh and Haokip both wake at the crack of dawn; Haokip to prepare for recruitment exams for public sector banks, and Dinesh to train for the Indian army. After classes, Haokip helps younger children with their homework for 4,000 rupees (about US$46) per month. A few months after the conflict began, Dinesh started a food stall outside the relief camp, where he earns an essential 700 rupees a day (about US$8) for his family.

The government “completely abdicated its responsibility to protect the civilian population,” says human rights activist Babloo Loitongbam.

The violence has wound down in the past year with the resignation of Manipur Chief Minister Biren Singh. Singh, a member of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, was accused of playing a partisan role in the conflict. The state has had no popularly-elected government since February.

Efforts to resolve the crisis are made in “bits and pieces,” says GK Pillai, India’s former home secretary. Peace will take time, he says.

There’s been no major violence in recent months, but protests in May and again in June underscored how fragile the peace remains.

For Haokip and Dinesh, the true challenge lies ahead: rebuilding their lives and returning home, across a line that remains, for now, uncrossable.

Editorial Team

Reporters:

Editor:

Researcher:

Copy Editor:

Photo Editor:

Angana Chakrabarti is a Shifting Democracies Reporting Fellow based in Assam, India. She covers politics in the Northeast region of India. In 2022, she won the Mumbai Press Club’s Red Ink Award for her reporting on the vandalism of mosques in Tripura.