CAP-HAÏTIEN, HAITI — When armed men invaded the Port-au-Prince neighborhood of Carrefour Feuilles in August 2023, hundreds of families had no choice but to flee.

“They set my house on fire; we couldn’t save anything,” says Ruth, a 28-year-old who was part of the exodus and now lives in Cap-Haïtien. “They looted and burned houses,” says Ruth, who asked to be identified by her first name to avoid the risk of reprisal.

In the rush, Ruth and her family took only their identity documents; she took refuge with relatives in Delmas, a Port-au-Prince commune, while her mother and three brothers found shelter in another neighborhood of the capital.

For Ruth, like so many others, it was the first step in a journey that is transforming Haiti. Driven by violence, dozens of people leave the capital every day to try to rebuild their lives in Cap-Haïtien, the country’s second-largest city. Ruth’s family finally settled there in September 2024. Ruth joined them six months later by plane, once she was able to obtain a transfer from her customer service job at a cell phone provider.

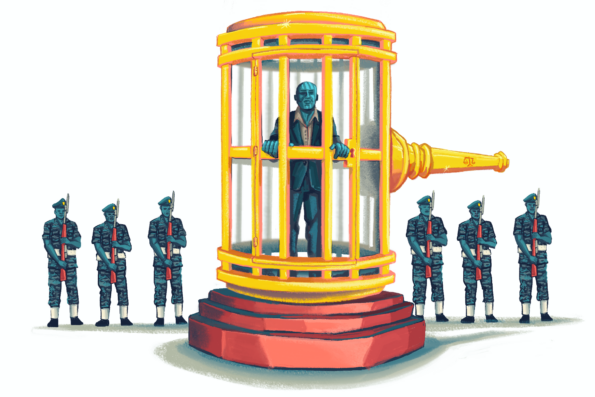

Port-au-Prince and other municipalities in Haiti are facing waves of violence linked to gang attacks, extrajudicial killings, kidnappings and gender-based violence. In 2024, the United Nations estimated that between 150 and 200 gangs operated throughout Haiti, with 23 active in the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area. The groups control strategic areas of the capital and the main roads connecting Port-au-Prince to ports, land borders, and certain cities and coastal areas.

According to data from the International Organization for Migration, more than 1 million people are now displaced within Haiti, with the majority originating from the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area. Many are seeking refuge in the Haitian provinces, overwhelming host communities.

In Cap-Haïtien, refugees from Port-au-Prince arrive at the Barrière Bouteille station, bustling with motorcycle drivers and street vendors, and often littered with trash and stagnant water. Phone thefts are sometimes reported in the crowd.

Donaldson, originally from Cité Soleil, one of Haiti’s largest slums, arrived in December 2023 after a long journey. His bus broke down numerous times along the way. An agronomy student who also asked to be identified by his first name, he had come to spend a few days’ vacation in the city. But what he thought would be a temporary stay turned into a forced relocation. With the rise in violence in Cité Soleil, where clashes between gangs and law enforcement have intensified, returning to Port-au-Prince has become impossible. Since then, Donaldson has enrolled at Anténor Firmin University and is living with a cousin.

“I’m continuing my studies here, waiting to be able to return to the capital one day,” he says.

Although she has no access to water or electricity at home, Ruth feels more or less safe now, with affordable health services nearby. However, there is a lot of prejudice against those who come from Port-au-Prince. Even though police data show no increase in crime linked to new arrivals, suspicion easily attaches itself to people from Port-au-Prince following thefts and burglaries.

“Some people call us the mafia, accuse us of destroying the country and bringing insecurity. When I hear these comments, I feel isolated, as if I don’t belong here,” Ruth says.

Faced with these tensions, local authorities are trying to manage the arrival of displaced persons. Many do not have identity documents, which complicates their integration into local systems.

“With the arrival of these new faces, our workload has increased,” says Arold Jean, spokesperson for the provincial police department. Of the more than 700 people arrested in January, more than 100 came from other regions of Haiti, Jean says, a reality that requires even more coordination with authorities across the country.

“We are also working to raise awareness among the population to explain how to welcome these people in good conditions,” Jean adds.

The city council, for its part, has set up a registration service enabling new arrivals to obtain a certificate of origin. This document is often required to rent accommodation or access certain services in the city. Since May, the police have also been asking public transport drivers to record the identities of their passengers.

Despite the insecurity in Port-au-Prince, Donaldson remains optimistic: “I’m living here for now, but if the capital returns to normal, I’ll be one of the first to leave.”

Wyddiane Prophète is a member of the Global Press Reporting Network based in Haiti.